Most of us diagnosed with MS wouldn’t consider that we could have a chronic silent malarial infection because we haven’t travelled to a tropical country that has malaria. Nevertheless, over 100 years of compelling scientific evidence links malarial infections to MS.

This research shows that for some and possibly many MS patients, a malarial infection is causing much if not all of their MS symptoms.

In the 2001 scientific journal article, Is multiple sclerosis caused by a silent infection with malarial parasites? A historico-epidemiological approach: part 1, researcher H. Kissler reviewed the observations of many researchers over more than 100 years.

He compared distribution studies of MS with those of other diseases and found that the only parasite that had similar distribution to MS was a plasmodium that causes malaria.

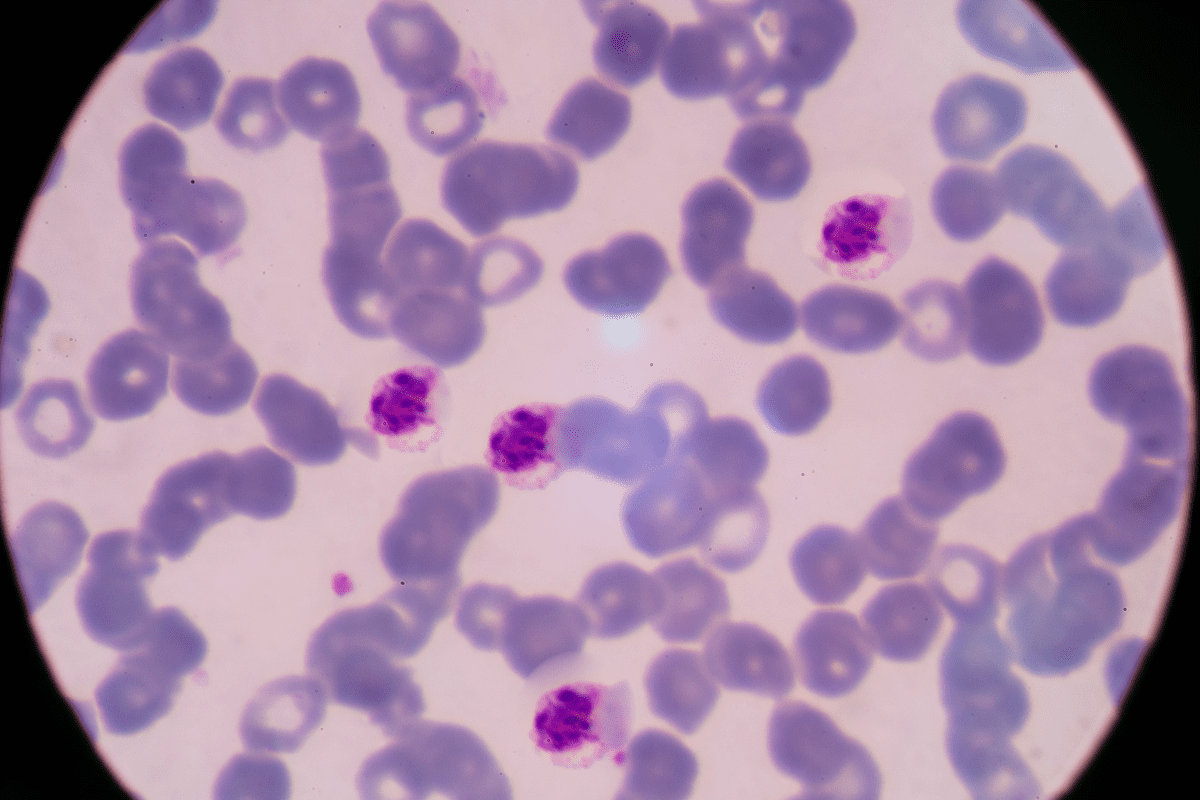

Kissler shared research that found antibodies against malaria parasites in 30 – 40% of MS patients and malaria parasites in about 20% of MS patients. This is very significant because when searching for malaria parasites in bloodwork, it is a well-known fact that it can be extremely difficult to find these parasites. Antibodies against malaria in the MS participants were mostly discovered on the first try. No antibodies against malaria were found in patients suffering from other diseases.

A separate study looking at the bloodwork of healthy people, blood donors and accident victims showed no antibodies against two strains of malaria.

All this evidence along with the similarities in symptoms of MS and malaria plus similarities in the distribution of malaria and multiple sclerosis all suggest that MS could be caused by a chronic infection of malaria parasites.

The results were remarkable because none of the patients had ever visited a tropical region that had malaria.

Important things to consider:

- MS was a rare, neurological disorder in the mid 19th century and today it is the most common disabling neurological disease in young adults.

- MS is rarely found in the tropical zone and in warm climates in general. The risk of MS increases gradually moving north of the equator towards the poles, but then decreases in the far north as seen in northern Norway, and Alaska.

- In some of the areas where there is a high incidence of MS, it is not distributed evenly but instead is scattered and in clusters, for example in Switzerland and Scandinavia.

In a 1936 textbook about malaria infections in humans that Kissler references in his article, cases of chronic malaria were characterized mainly by neurological symptoms which often resembled MS but typical malarial fever was not present and the parasites were very difficult to detect.

He also draws attention to the authors of a 1963 textbook studying malarial disease in humans who wrote that the most common neurological symptoms of malarial infections included slow speech, tremors, spastic gait, muscle twitches, involuntary eye movements and reduced vision and depth perception which affects balance and coordination.

In Kissler’s journal article, he mentions that in 1889, neurologist Prince reported on six cases where malaria was followed by MS. He later found another 3 patients for which this was true. Most of his patients had contracted malaria while serving as soldiers in the southern USA during the Civil War.

Kissler also shared the findings of researchers who compared a map of the worldwide distribution of malaria to a map of the worldwide distribution of MS. Where malaria was an endemic disease there was no MS. There was also a gradual decrease in MS and an increase in the incidence of malaria if one moved from north to south in the northern hemisphere. The same was true, vice versa, for the southern hemisphere. The author suspected that one disease was extinguishing the other.

Where malaria was endemic in the US between 1929 and 1938, there had later been fewer cases of MS. And MS patients treated for malaria had significant improvements.

Is it possible that areas with a high prevalence of malaria have a lower incidence of multiple sclerosis because malaria is recognized and treated well in those areas?

Because the chronic silent malaria form of infection is uncommon and overlooked, it has been almost forgotten in current textbooks of malaria and therefore it is not surprising the term “malaria” is not mentioned in MS textbooks and thus neurologist don’t consider malaria when diagnosing MS.

It’s sad that this research has been largely dropped for many years, but with the new study below from the University of Calgary, Alberta, Canada, hopefully interest in this field will be renewed.

MS News: Malaria Drug May be a Promising Treatment for PPMS

There are Real Solutions for MS Today!

To restore health, we must focus on treating the cause of inflammation, which are parasites. First, identify the enemy (parasites), then support the body and treat the parasites while following a holistic approach. When parasitic infections are treated effectively, we can overcome inflammation or disease.

If you’re frustrated with the fact that our standard of care STILL doesn’t offer a real solution for treating MS, then click on the link below to watch Pam Bartha’s free masterclass training and discover REAL solutions that have allow Pam and many others to live free from MS symptoms.

CLICK Here to watch Pam’s masterclass training

Or take the Health Blocker Quiz to see if you could have parasite infections

References:

Clinically diagnosed with multiple sclerosis at the age of 28, Pam chose an alternative approach to recovery. Now decades later and still symptom free, she coaches others on how to treat the root cause of chronic disease, using a holistic approach. She can teach you how, too.

Pam is the author of Become a Wellness Champion and founder of Live Disease Free. She is a wellness expert, coach and speaker.

The Live Disease Free Academy has helped hundreds of Wellness Champions in over 15 countries take charge of their health and experience profound improvements in their life.